There’s a bit of irony in the phrase Operation Warm Welcome, in that it implies that we are extending a helping hand to those in need simply out of the kindness and purity of our hearts. But anyone who is familiar with what the ‘Operation’ was, will know that it was merely to support those through turbulent times who have availed us of their assistance. Even then, it could be argued that it wasn’t a very sincere attempt at assistance.

However, the point of this discussion is not to discuss whether or not Operation Warm Welcome was genuine or not. What is worth considering though, is whether it has been successful and whether the UK can look to it as a replicable example in the future.

Operation Warm Welcome was the proud creation of the Home Office in 2021. It followed Operation Pitting, which primarily involved the evacuation of those Afghans who had supported the British (whether it was through embassy operations or through other government affiliated organisations such as the UK Armed Forces). The Operation was established to ensure that all of those who were evacuated from Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover were resettled and relocated in the UK.

Operation Warm Welcome is the umbrella term, and breaks down into two once those being supported arrived in the UK. The first is termed the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (or ACRS) and the second is known as the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (or ARAP).

Prima facie, the two schemes seem reminiscent of each other. It becomes easy to quickly conclude that the Home Office are pulling a fast one on us by coming up with two fancy names. However, prior to making any rash judgments, it is worth addressing the two in further detail.

This scheme is for Afghan citizens who ‘worked for or with the UK Government in Afghanistan in exposed or meaningful roles and may include an offer of relocation to the UK for those deemed eligible by the Ministry of Defence and who are deemed suitable for relocation by the Home Office’[1].

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/afghan-relocations-and-assistance-policy/afghan-relocations-and-assistance-policy-information-and-guidance

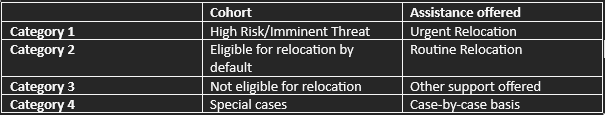

Seems rather simplistic until you realise that this explanation has been broken into categories under which an Afghan must fall to be availed this ‘warm welcome’.

Now, through a quick analysis of these categories, the first and second make relative sense. However, the difference between Category 3 and 4 is practically invisible, to the point that it makes you seriously the Home Office is obsessed with categorising everything.

Category 3 is the most frustrating of all. Firstly, how can a cohort which is ‘not eligible for relocation’ fall eligible under a resettlement scheme? Secondly, there is absolutely no explanation on what ‘other support offered’ consists of, unsurprisingly leaving those who fall under this category in a limbo.

In order to be eligible under this scheme, you must fall under one of the following ‘pathways’ (note the fancy terminology used):

Vulnerable and at-risk individuals who arrived in the UK under the evacuation programme first have to be settled under the ACRS. Eligible people who were notified by the UK government that they had been called forward with assurance of evacuation, but were not able to board flights, and do not hold leave in a country considered safe by the UK.

Those vulnerable refugees who fled Afghanistan for resettlement to the UK and have been referred by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

Those who are at risk who supported the UK and international community effort in Afghanistan, as well as those who are particularly vulnerable (women, girls and those from minority groups).

Priority under this pathway is given to those at-risk people from:

3. Chevening alumni (those who have been recipients of scholarships or fellowships through this programme)

Through the differentiation of the two schemes, it would be seemingly foolish to contend that these are two different schemes and attending to a wider range of vulnerable Afghans. The reality is, however, that ACRS just builds on ARAP.

It is appreciated that the former extends protection for those referred to the UK government by the UNHCR. It is demonstrative of respect for the body which is particularly important given their policy disagreements relating to the Illegal Migration Bill.

However, the explicit mention in Pathway 3 of the extra protection to women, girls and those from minority groups seems a mere attempt to pacify. Given that ARAP is for any people who have worked with or for the UK government, surely women, girls and those from minority groups would be eligible for protection and relocation by default. It is an implied measure of the creation of ARAP. Its mention in Pathway 3 consequently become null, and one can only assume those preparing ACRS did not research its sister scheme in-depth.

At the end of their description of ACRS, the Home Office proudly claims that it ‘demonstrates the government’s New Plan for Immigration in action, to expand and strengthen our safe and legal routes to the UK for those in need of protection’. There is no doubt that the schemes were created with their agenda of reducing ‘illegal’ migration borne in mind.

The question to be posed, however, is whether there is any success in the affording of adequate protection to those fleeing the Taliban takeover.

Now, important to note is that when these vulnerable Afghans entered the UK through the above-mentioned schemes, they were housed in ‘bridging accommodation’. These have been officially defined as:

“all accommodation procured by the Home Office for the purpose of providing temporary accommodation for those evacuated to the UK as a result of the events in Afghanistan following the fall of Kabul in August 2021”.

Put simply, ‘bridging accommodation’ constitute hotels bear unfortunate resemblance to those which hold other asylum seekers.

The Home Office further qualify in their guidance that this is not intended to be a settled solution. So, in March of this year, they announced their plans to end the use of bridging accommodation.

The issue which arose, however, was that all of these vulnerable people would have no place to live once bridging accommodation seems to be used. A seemingly obvious oversight, no doubt. However, it lead around 8,000 individuals being presented with eviction notices; one in five of whom have already been evicted and counted as homeless.

The Home Office solution? Delegate, of course. It became the responsibility of local councils to secure private rentals to house vulnerable Afghans who have left their homes behind to seek safety. It is also worth remembering that local councils are expected to house 8,000 people in the middle of one of the UK’s worst housing crisis. There is no doubt that this decision is just the effect of policy makers realising that they did not think their ‘New Plan for Immigration’ through – unsurprisingly forgetting that support is supposed to extend beyond the immediate emergency of August 2021.

What is essential to note, and honestly shocking, is that local councils are to volunteer themselves and whether or not they are willing to secure private rentals within their districts. The incentive would be that they would receive a portion of the £250 million placed aside for this purpose by the government, depending on the number of Afghan refugees who are supported.

Where the assistance scheme is delegated to councils who have to volunteer themselves after being attracted as a result of financial incentives, any genuine attempt becomes a reckless attempt. Unfortunately, this is exactly what the consequence of ‘Operation Warm Welcome’ has become. Prominent members of British politics and armed forces who may once have availed the UK government’s effort in August 2021 now call its effects ‘shameful’[1].

[1] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/afghan-refugees-evictions-hotels-b2387908.html

The will to present ourselves as strong and ‘world-leader like’ is blatant in the creation of ACRS and ARAP. It follows the pride seen during Operation Pitting itself. But what ensues is merely proof of a greater façade. It seems as though the will to support and integrate vulnerable refugees into British society was a fleeting thought, if any. Any appreciation of their assistance to the UK seems quickly forgotten. In light of this, it is possible to conclude that Operation Warm Welcome may form a template for future emergencies. However, it should be referred to loosely and more of an attempt should be made to learn from its mistakes.

Unfortunately for those 8,000 who believed they would live a safer, more comfortable life here in the UK, Operation Warm Welcome isn’t as warm a welcome as it should have been.

Should you need guidance pertaining to your Individual, Business or Humanitarian UK immigration matter,

To arrange meeting with our lawyers, contact us by telephone at

+44 2077202156 or by email at office@goodadviceuk.com.

If you have instructed us before, we would be pleased to know your feedback about your experience.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |