For October, fine dining businesses have indicated that they are facing closures due to skilled staff shortages caused by Brexit and covid effects.

While the Evening Standard has also attributed this crisis to early retirees. I personally agree with their statement regarding the fate of UK business owners; it would be a real shame if sectors like leisure and hospitality manage to survive both the demand-side effects of Brexit and a pandemic, but not a shortage of workers. This week, we will cover the current state of the UK labour market with an analysis of points of improvement in sponsored visa routes.

Workers’ movement across borders in the 90s was not so much of a talking point practically anywhere compared to now. The pizzeria I frequented as a student has retained most of its staff even after several years, which is uncommon nowadays. ‘Brick and mortar’ or not, seeing a constant stream of different faces in non-corporate establishments have become commonplace.

Returning to my introduction, the skill sets that used to exist within the workforce are now becoming extinct, and that recruiting and retraining inexperienced workers has become the norm. Service providers have gone as far as shortening their work hours amidst efforts to locate skilled staff. Trade bodies estimate staff shortages cost significant amounts to the UK’s major sectors, including hospitality, tech, and healthcare, at as much as £21 billion. With the current economic and political shifts, the matter is not about vacancy but a shortage of necessary skills.

The skill gap within the UK has been a longstanding source of labour shortages for more than 20 years. According to leading consultants McKinsey, there has always been a mixture of soft and hard skill deficiencies in problem-solving, communication, customer care, and IT literacy.

According to the Industrial Strategy Council, 20% of the UK labour market is projected to be under-skilled. At the same time, about a million workers will be classified as over-skilled by 2030. The under-skilling not only comprises digital skills but also being acutely under-skilled in at least one core management skill and at least one STEM workplace skill. These are only some of the deficiencies the country’s workforce faces, which force employers to seek overseas talent.

To confirm the matter is about skill and not vacancies, Britain’s unemployment has recently been said to be at its lowest since the 1970s, and the seasonally adjusted values for June and August 2022 seem to have been about 0.4% lower than pre-pandemic levels of the same period:

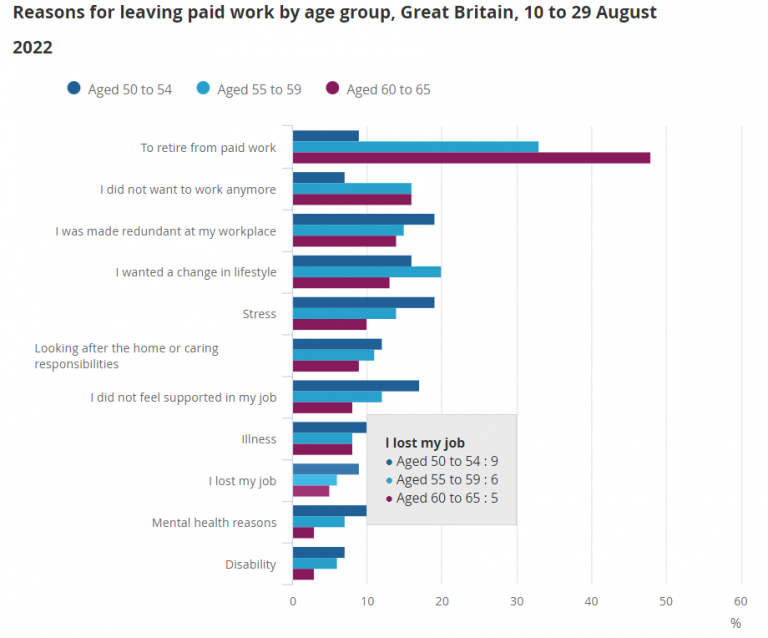

Furthermore, there has been a particular emphasis on inactive workers in the labour market, where there were about 400,000 more economically inactive adults aged 50 to 64 compared to pre-pandemic levels. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the older portion of this group was keen to retire due to age, against the younger group’s intent to leave their posts due to stress and a lack of support:

Overall, service sectors seem to be the most affected. Adaptation issues towards new technology brought about by digital transformation or being able to cook local cuisines while adhering to meticulous standards (i.e., Michelin) pose a considerable entry barrier to those who are a part of the sector but not quite there in terms of skill. The National Health Service (NHS), for example, remains obscenely vacant as the largest domestic employer due to both low graduation rates and considerable burnout in the workforce due to the pandemic. As The King’s Fund suggests, there is an immediate need to tackle this vicious cycle of shortages and increased pressures on staff, which in the short term can only be alleviated by introducing as many skilled staff as humanly possible.

Against this backdrop, the UK government intended to bolster these efforts post-Brexit by reworking and reintroducing a variety of work visa routes, including the Tier 2 Skilled Worker route, alongside:

Feedback from the public has not been so stellar, however. Workers who would like to apply for a visa are required to obtain a Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) from their potential employer, who must have been granted a Sponsor Licence before they can issue a CoS. As time has passed, it has become clear that the hurdles employers must go through to sponsor skilled workers have become mini-projects themselves, suggesting copious amounts of red tape. Currently, the added bureaucracy is so much of a problem that immigration law firms are providing personalised guidance to sponsors and workers alike [1].

This has arguably stemmed from the initially conservative stance of the government towards migrants, which loosened over time as the socioeconomic effects of an outflux of existing foreign and British workers became apparent and the demand for workers piled up. Initially, the minimum salary requirement to become eligible for a UK work visa was much higher at £30,000. Over time and with the external effects of Brexit and the coronavirus pandemic, the salary requirement was lowered by about 17% to meet the lowering skill threshold to admit workers in middle-skilled jobs. In a way, this reflects the government’s awareness towards the abovementioned deficiencies in the face of uncertainty.

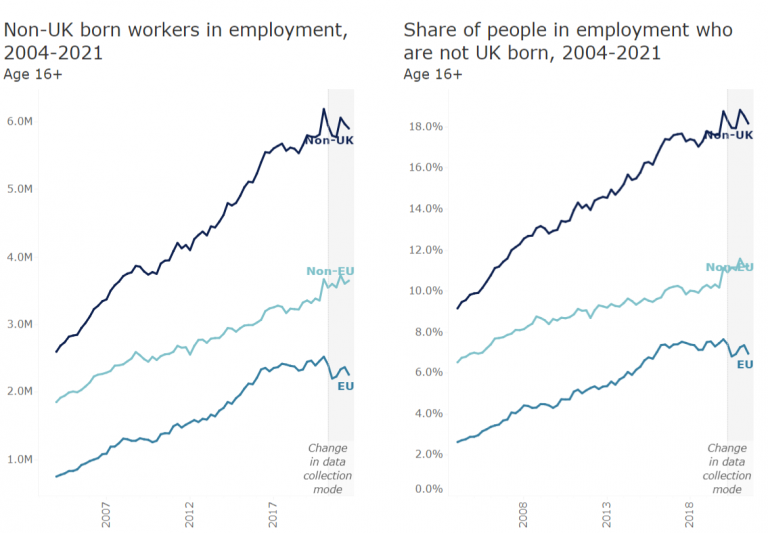

Lower pay could be another argument for why UK employers seek overseas workers. Considering the frequent argument over pay scales lowering due to settled migrants in the UK, an easy online search would prove that academic research has consistently refuted this. The London School of Economics indicated that immigrants have skills that complement UK-born workers and they, like everybody else, consume goods and services. From an economic standpoint, this increases demand and presumably contributes to more vacancies. However, it should be noted that non-UK and even non-EU-born workers in employment have been around for a long time, suggesting workers from abroad consistently bore the necessary skills to satisfy UK-based employers’ needs:

Excluding construction, as this is the sector this argument is usually built on, the impact of immigration on existing worker wages is argued to be mostly minimal. Actually, immigration’s widespread effect is specifically on low-wage earners regardless of the sector. In favour of this argument, the current government has somewhat created a barrier to immigrant wages by introducing ‘going rates’, a list of yearly and hourly minimum wages employers need to pay for each occupation. However, these are dependent upon factors such as the worker’s university graduation date and their occupation, as the same government has also introduced concessions to occupations in serious shortage.

Although all these are valid, what are the possible solutions? It is clear that sponsors desperately need incentives, as they prepare a series of documents to prove the genuineness of proposed vacancies and their businesses.

From the workers’ side, it is more about the constraints posed by the ‘skilled occupations’ list than salary ranges. ‘Skilled’ occupations predetermined by the government do not have an awareness of other skilled jobs in the same or parallel fields. One clear indication that these tiers are not working was seen in the September 2022 changes posted by the Home Office, where poultry was just added as an option for seasonal workers. A field as core as poultry should not be perceived as much of a niche, just because the government suddenly remembered its existence. Therefore, the skilled occupations list is definitely in need of a revamp. Control could be relinquished slightly in favour of the sponsors themselves, and the licence system could provide them free rein and responsibilities in exchange for less scrutiny from the Home Office’s side.

In summary, the abovementioned remedies will take time, investment and the facilitation of several infrastructure projects that can only be a part of a long-term plan with set goals. As a band-aid solution which may at least buy some time, the current immigration system is welcoming towards both temporary and lengthier roles with longer durations with a window to settlement.

Conversely, the long-term plan would be to focus on training and educating UK-born workers from a young age. This seems to be a safe footing for any political party that safeguards the interests of the public.

For more information on business visas, particularly in obtaining a Sponsor Licence to recruit skilled workers from abroad or to be sponsored by your potential employer, contact us to book a consultation.

[1] We recently began covering several sponsor routes and their nuances in our blogs, such as this one:

‘8 Mistakes to Avoid When Applying for a UK Sponsorship Licence’

Full Fact – What does immigration do to wages?

Industrial Strategy Council – UK Skills Mismatch in 2030

The King’s Fund – NHS workforce: our position

NFU Online – Poultry seasonal worker visa labour providers confirmed

ONS – Increase in economic inactivity in those aged over 50 years

UK Parliament – Statement of Changes in Immigration Rules

Reuters – UK labour market exodus drives jobless rate down to 3.5%

Evening Standard – Trade bodies estimate staff shortages cost hospitality £21 billion

The Guardian – UK unemployment is lowest since 1974 but workers face pay squeeze

ONS – Reasons for leaving paid work by age group, Great Britain

Migration Observatory – Migrants in the UK Labour Market, An Overview

To arrange meeting with our lawyers, contact us by telephone at

+44 2077202156 or by email at office@goodadviceuk.com.

If you have instructed us before, we would be pleased to know your feedback about your experience.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |